|

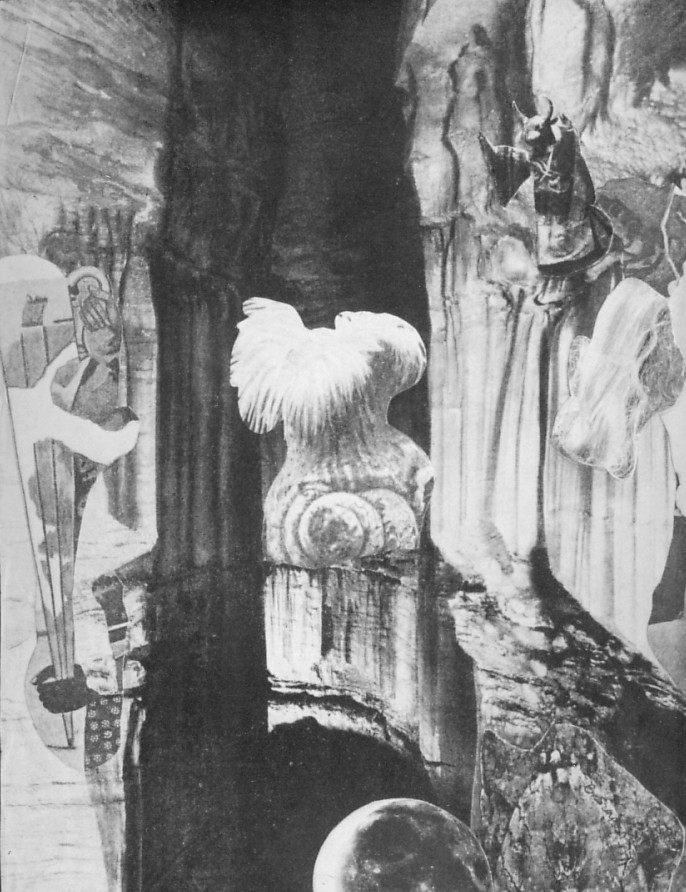

Cave of the Mandarins

.

Adroit cartographers

over the centuries have learned to communicate by inserting discrete

visual

clues or codes into their maps. An expert in the discipline can pick

them out

and, from time to time, discussion about them has entered into

scholarly

discourse, even if the practice is more playful than serious. Scholars

must

laugh like the rest of us.

That they do so amidst

arcane analyses for a small audience comes as just another

flourish in an otherwise routine culture that

the academy prizes.

Recently, linguists

from the University of Modena, Italy, have applied new translation

techniques

to this exclusive tradition. Coupling algorithms refined to detect

subtext and

structure in comparative groups of visual signs with newly conceived

oneiric

interpretations, they have produced a quixotic yet compelling narrative

that

has unearthed some disturbing values.

Maps portray

landscapes, natural and urban. They also portray something of the

dreamlife

that unconsciously goes on when awake, and which, however much

cartographers

guard against it, seeps into their work. This does not mean that their

maps are

incorrect. They aren’t, given the historical period in which they drew

their

maps and the information they had to draw them. It does mean, however,

that

cartographers knew or felt or intuited, as they drew, that the line,

circle,

squiggle or vector spoke to them in a language that the clues or codes

they

left on the map referred to.

Here, though, is what

our linguist group has found.

Figured bodies of land

or water, outlined and inset with geographic features – such as plains,

lakes,

rivers, highlands, mountains, valleys, islands and the like – provoke

erotic

images; a tendency quite natural to us and which, I must admit, is a

predilection of my own. When viewed straight on or obliquely, images

emerge.

And however blurred or haphazard they might appear at first, a kind of

latent

visual subtext, more pronounced here, less pronounced there, they

slowly

clarify and then, as if part of the pulsation that keeps us alive,

disappear. A

slow natural flickering subsumes the map. Suggestive couplings, routine

seductive poses, wide glistening ecstatic eyes, moist curving lips,

full

breasts, an erect penis, a tangled vagina, the bare shoulder that

slopes to the

top of the arm, a hand with long reaching fingers, the slope of the

ankle, a

turned wrist, a sweaty cheek and other anatomical signs, many of which,

beyond

their status as cultural clichés, suddenly compel; transforming

the map into a

palimpsest of desire, both compassionate and cruel. Apparently, the

visual

clues or codes that cartographers inset into their maps attest to this

unique

facility, this envisioning, by drawing our attention to different areas

whose

boundaries interact. And what was once a recognizable geographic shape,

complete in itself, alters.

The terrestrial

cartography of surficial bodies becomes a medium that allows viewers to

see, as

it rises and as it passes, what attracts them most in this infectious

momentum.

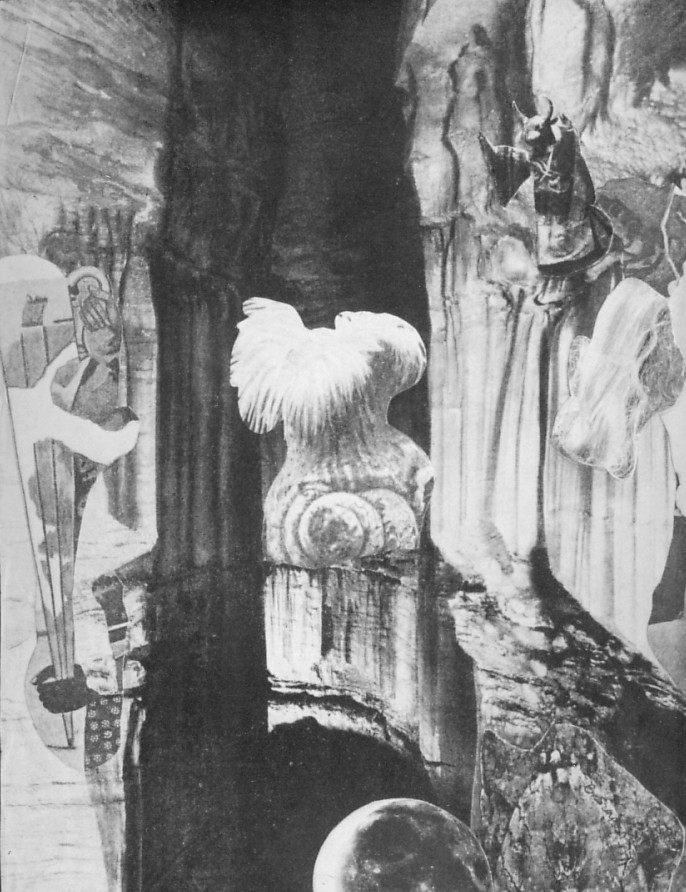

The study group has also noted an eccentric disposition that figures,

not

humans, but animals in rut as well as large insects whose mating

choreographies

are as complex as they are savage, with death and ingestion a

concomitant

outcome; the female its dominatrix. Whether or not the translation of

other

animate creatures into visible images will occur, how they accord with

their

roles in nature, what sex leads and what sex follows, which is prey to

instinctual hunger, whether or not mimicry, masking and nurturance

claim their

pedigree are questions, surely among others yet defined, for further

study.

One result, however,

is fairly clear: The envisioning that researchers have developed leads

them and

us into realms, both imaginary and real, that refract individual

passions while

valorizing anew our capacities in mapping. At the same time, the

technique is a

risky one, especially when it prompts the viewer to enact what he or

she has

seen without the usual cautions in place, preferably in a palace built

for that

purpose or, if lacking, then on any stage suitable for what’s to come,

luxurious or plain, large or small.

Gregg

Simpson

and Allan Graubard

|

|